How do we stop subway surfing?

In the time since I first wrote this, Seung Lee has written a far better piece, and I think that leaving my piece here without first instructing readers to read Seung’s would be irresponsible and in bad faith. You should go read that here. The text of my piece is below the fold.

Content warning: this article talks about death (though not in detail). It also talks about acute mental health issues and other potentially upsetting topics. It may be triggering. If you need help, call or text the crisis hotline: 988.

As the Bay Area begins to see more instances of people riding outside of trains, and as I prepare to move to the East Coast (most likely New York City), I’ve been thinking a lot about “subway surfing” and how to stop it (and why the things we’ve tried haven’t worked), and I wanted to put those thoughts into writing.

I hope this piece can help facilitate more conversations about this problem, but it is not a super researched piece. What I will write about here is mostly a collection of my thoughts, and takeaways from my discussions with friends, both inside and outside of the transit industry. If you’re a journalist, or are in the industry, or have thoughts on this, shoot me an email.

“Subway surfing” is the popular term for riding outside of designated passenger areas on trains (roofs, couplers, between cars). This term is problematic in itself. Obviously, this is super dangerous, and the consequences are dire. The last few years have been a substantial uptick in the number of incidents of people riding outside of trains, but the problem isn’t new. Surfing has been documented on the New York City subway. It first emerged as a hobby1 in New York City (and South Africa) in the 80s. Almost immediately, deaths started happening.

It is the most deadly trend to become popular among youth in a long, long time. Subway surfing involves hundreds of factors outside of ones control. If any of those hundreds of dice roll wrong, the consequences are death or serious injury. Tracks are electrified, tunnel clearances are low or zero, and trains move fast.

Who and why? #

The vast majority of people who subway surf are young, shockingly so. Generally, they are high schoolers or recent high school grads, 15 years old to late twenties, and usually male. An article in Curbed tells the story of a recent high school graduate in New York City who used to surf trains, but stopped after multiple of his friends died surfing.2

Nowhere is this epidemic worse than in New York City, where the MTA tracked more than 450 incidents of individuals riding outside trains just between January and June, 2023.3 Though this problem exists elsewhere,4 I’m going to be talking a lot about New York City, because nowhere has the problem been more pronounced and the failure to address it more acute.

How we got here #

Despite happening since the 80s, surfing has increased massively in the last couple years. The main driver of this growth has been social media, which has catapulted a formerly niche activity done by those on the fringes of society into a trend. TikTok and Instagram are the main culprits, where subway surfing videos go viral, with dozens garnering millions of views. This virality and the temptation of social clout compel more and more people to take up subway surfing.

(Social) media coverage #

Surfing has become cool,5 and as more and kids are seeing their peers do it, and deciding to try themseles, more and people are ending up dead. Often, kids start because they see others doing it on social media. They talk about it at school6 and post videos and pictures of themselves doing it on social media (mostly Instagram and TikTok). According to the man interviewed in the Curbed piece, surfing appeals most to kids who have bad home or school lives. He started surfing “to escape ‘issues at home.’”7 As the youth mental health epidemic continues to worsen, and as social media continues to amplify videos of surfing, it will get worse and worse, causing more deaths and trauma.

But surfers find both the act itself, and the social media clout they get from it addictive, and get hooked after their first time, says the interviewee.

Another culprit is the media. Nearly every major outlet in New York City has run flashy headlines about surfing. With the press’s help, what was once a niche, unknown hobby has become a commonplace topic of discussion, boosting its reach a thousand-fold. If it weren’t for the press’s careless coverage (and bad faith calls to action) and social media, surfing would not be the epidemic it is today. We’ll talk about the press more later.

What New York tried #

Faced with increasing pressure to do something about subway surfing, the MTA launched a big, loud, flashy campaign of PSAs, outreach, and messaging in September, 2023.8 The campaign involves frequent, system-wide PSAs in the subways from kids, trying to make subway surfing seem not cool. They include slogans like “ride inside, stay alive,” “this is the subway, not Coney Island,” and other flashy soundbites. If you’ve ridden the subway recently, you know how annoying these announcements are, and how many eye-rolls they elecit from young riders. Much like the post 2015 anti-vaping ad campaigns, it has been ineffective. Worse: subway surfing incididents have gone up. We know mimicking DARE tactics won’t work,9 so why is the MTA doing it?

MTA’s campaign is a response to claims by the mayor and the media that MTA is at fault, and that they aren’t doing anything. Motivated more by wanting to look like they’re doing something than logic, it is failing.

There are a couple reasons MTA’s approach is failing:

- Kids don’t like to be told “no.”

- It doesn’t make surfing harder.

Anybody who has ever worked with kids knows that kids don’t respond well to being told not to do something by an authority figure. Being told no only makes them want it more. It becomes rebellious and edgy to go against what you’re told. This approach makes subway surfing seem cool. This DARE-style “just don’t do it” approach that relies on scare tactics doesn’t work,10 and represents a failure to target this kind of messaging at the people it needs to reach. The content of this campaign might be reassuring to the people who want something to be done, but they fail to reach the people who really matter: surfers. Most kids know not to surf, and the ones who are brave enough to try feel challenged, not dissauded. They know it’s dangerous, to them, that’s part of the appeal and pointing it out is useless at best and counterproductive at worst.

It is possible to reduce the amount of people surfing through effective, carefully planned, targeted outreach, but this is not that.

The fact that this messaging won’t positively impact the people who surf, and the fact that MTA hasn’t introduced any new physical barriers to surfing (while increasing awareness of it among kids!) explain this campaign’s ineffectiveness.

What is there to be done? #

It feels like a bleak situation. Aside from funding and staffing, surfing is arguably the biggest problem facing large and mid-size transit agencies in the U.S. right now. But there are things that can be done.

Making surfing uncool, not taboo #

As long as subway surfing remains something that “the man” is telling kids not to do, it’ll continue to be cool to do it. It’s a fine line to straddle, but subway surfing needs to be made uncool instead of taboo.

Transit agencies should adopt better detection and reporting methods. If a train crew is made aware of someone riding outside the train, the train should stop and discharge all of its passengers at the next station. Announcements should be made informing passengers that the train is being taken out of service due to people riding outside the train (it can go back into service at the next stop). This will make passengers angry. It’ll make subway surfing seen as more of an antisocial behavior, and it will become stigmatized and uncool. It’s hard to feel cool after making 1,000 people mad at you because you messed up their commute. Another benefit to taking trains out of service is sending the message that if you are caught surfing this train, you will not be able to continue surfing this train.

Secondly, agencies need to be much more careful about their messaging. Snarky PSAs like those played on loop by MTA are counterproductive, and make kids want to rebel. If anti-surfing PSAs are going to be deployed, they should be short and succint: “riding outside of subway cars causes delays.” They should be not be patronizing or able to be seen as a challenge by potential surfers.

Responsible journalism #

The media has played a big role in creating this problem, and it needs to behave more responsibly for things to get better. The media reports on subway surfing a lot like they report on school shootings: incorrectly. They describe in detail the actions of surfers, they include pictures and video of surfing, they use the term “subway surfing”11 incessantly, they include pictures and names of people who do it. They lionize surfers and give them noteriety, which only makes more people surf more often. If you’re a reporter or an editor, here’s what you can do:

- No flashy headlines.

- Avoid talking about surfing when reporting on surfing fatalities. Simply say that somebody died after riding outside a train.

- Avoid lionizing surfers, both dead and alive.

- Never show photo or video of people surfing.

- Don’t blame the transit agencies. This kind of pressure causes reactions like NYMTA’s, which is reactionary and a failure.

- Highlight the delays and trauma caused to operators and other passengers.

Physical deterrence #

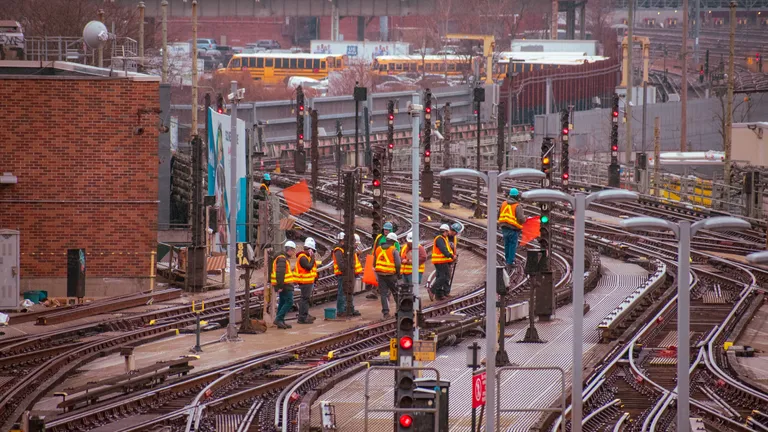

In New York and the Bay Area, people often surf by climbing onto trains from within the space between cars. Fortifying these gangways so that they’re harder to climb out of, and in the long term, acquiring fully sealed, open gangway trains like the R211T where getting from the inside to the outside of the train is nearly impossible.

Agencies should invest in better detection systems to detect people riding outside of trains sooner. If at all possible, remove things that allow people to climb onto trains, fortify gangways, make train roofs slippery. In San Francisco, Muni can invest in coupler-covers to shield the couplers on the front and back of their LRVs.

Social media moderation #

The biggest piece in this puzzle is social media. Currently, social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram, do little to nothing to quell the surge of surfing and conquesting videos. I’ve reported such posts hours after they were posted. By the time Instagram even responded to my report (deciding not to do anything), the videos had been shared and reposted multiple times and racked up thousands of views. We know Instagram and TikTok are capable of fast, effective deplatforming of certain topics, as is evidenced by their ability to censor pro-Palestinian content with high accuracy.

By the time Instagram responded to my appeal to their decision to not remove the post, removing the post, the video had gained hundreds of thousands of views. This is typical for surfing videos. Unfortunately, in the case of the most recent trackside fatality on BART, two large Bay Area focused Instagram accounts reposted the initial surfing videos, encouraging the young poster to keep doing it.

Peer-to-peer #

Kids aren’t responsive to “the man” telling them no. If they’re going to hear it, it needs to come from people their age who they will find relatable. Kids who lose friends to surfing should be given a platform to talk to other kids.

Thanks for reading. If you have thoughts, or are an agency/journalist, you can get in touch with me by email.

“Hobby” used very lightly. ↩︎

I’m not linking to this article, because, despite including some valuable insights, it shows a lot of images of surfing, which I don’t want to spread further. ↩︎

Mayor Adams, Governor Hochul, MTA Launch “Subway Surfing Kills – Ride Inside, Stay Alive” Public Information Campaign press release from September 5, 2023. ↩︎

As of writing, there have been two deaths in the Bay Area this year. This is a problem plagueing many large and mid-size transit agencies, and is not just restricted to heavy rail operators. ↩︎

As have other anti-social subway-related activites, like “conquesting”. ↩︎

Incidients of individuals riding outside of trains on the New York City subway peak during after school hours on warm days. ↩︎

He says by 16 he was diagnosed with anxiety, ADHD, PTSD and despression. ↩︎

See footnote 4. ↩︎

‘Just say no’ didn’t actually protect students from drugs. Here’s what could, from NPR. ↩︎

Scare tactics (like those employed by pre-2015 anti-smoking campaigns) work well on most people, but miss people already on the fringes with higher danger tolerances, who feel challenged by them. ↩︎

Yes, I’m guilty of that here too. The term makes it sound fun, epic and cool, which works as cross purposes to our goal of making it uncool. ↩︎